Imagine the chaos: three different people holding the highest office in the nation within the span of 365 days. It sounds like a constitutional crisis, but it actually happened twice in American history—in 1841 and again in 1881. Both years were marked by tragedy, unexpected presidential deaths, and a glaring lack of clarity in the laws of succession.

The First Crisis: The Year 1841

The chain of events in 1841 was unprecedented because it had never happened before: a President died in office.

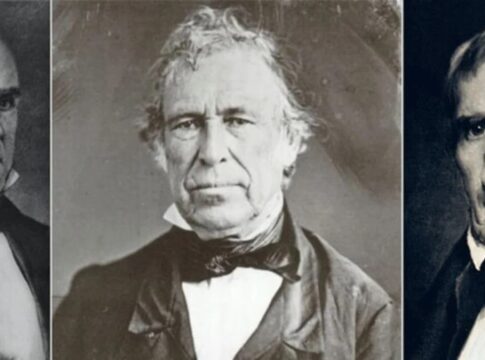

- Martin Van Buren finished his term on March 4, 1841.

- William Henry Harrison was inaugurated on March 4. At 68, he was the oldest president elected to date. Tragically, he died just 31 days later, on April 4, after contracting pneumonia.

- John Tyler was the Vice President, and his move into the White House caused a massive constitutional headache.

The Constitution stated that in case of the President’s death, the Vice President’s duties and powers would devolve upon him. But did he actually become the President?

Tyler asserted unequivocally that he did. He refused to be called “Acting President,” setting a powerful “Tyler Precedent” that was followed for over a century. He essentially interpreted the ambiguous clause to mean a complete, non-temporary transfer of the office, securing his full executive authority.

The Second Crisis: The Year 1881

Forty years later, the nation endured the same instability under much more tragic circumstances: an assassination.

- Rutherford B. Hayes finished his term on March 4, 1881.

- James A. Garfield was inaugurated on March 4. Just four months later, on July 2, he was shot by a disgruntled office seeker at a railroad station.

- Garfield did not die immediately. For 11 weeks, the nation was thrown into turmoil as the President lay incapacitated, with no clear constitutional mechanism for transferring power while the President was unable to serve. He finally died on September 19, making Chester A. Arthur the third man to occupy the office that year.

Arthur’s transition was politically difficult. He had been a product of New York’s corrupt political machine, and many in Congress doubted his ability to lead. However, like Tyler before him, Arthur asserted the full power of the office and ultimately surprised the nation by championing civil service reform.

The Enduring Legacy of Uncertainty

These two crises revealed a serious flaw in the U.S. constitutional framework. The ambiguities exposed by the deaths of Harrison and Garfield demonstrated two needs:

- Clarity on Succession: The Vice President needed to be confirmed as the President, not just an acting placeholder.

- Incapacity Protocol: There was no way to transfer power if the President was alive but too ill or injured to govern (as happened with Garfield).

These gaps led to over a century of legal and political debate, finally culminating in the ratification of the 25th Amendment in 1967. This Amendment formally cemented the “Tyler Precedent” and, crucially, established procedures for both filling a Vice Presidential vacancy and temporarily transferring power when a President is disabled.

Without the tragic events of 1841 and 1881, the rules governing presidential stability might never have been clarified, leaving the nation vulnerable during times of crisis.

It’s amazing how much 19th-century misfortune shaped the modern legal structure of the executive branch! Would you like to compare the political impacts of Tyler’s presidency versus Arthur’s?